In Search of Bottesini

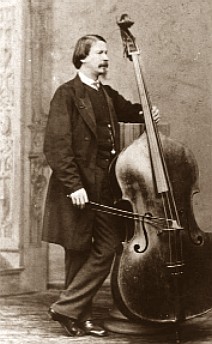

Tom has always had a keen interest in the key double bass composer Giovanni Bottesini and produced this celebrated work about the maestro.

Thomas Martin - In Search of Bottesini

Part 1 - Page 1

My interest in Bottesini began only a few years ago (in about 1980) when my circumstance and especially my health allowed me to become interested in solo playing on the double bass and in the compositions of Bottesini in particular. This fascination grew to a desire not only to learn what I could about his music but also to an interest in the man himself as a person, player, and composer. Here, then, is an article not by a scholar or educated writer, but by a simple bass player in search of Bottesini.

My interest in Bottesini began only a few years ago (in about 1980) when my circumstance and especially my health allowed me to become interested in solo playing on the double bass and in the compositions of Bottesini in particular. This fascination grew to a desire not only to learn what I could about his music but also to an interest in the man himself as a person, player, and composer. Here, then, is an article not by a scholar or educated writer, but by a simple bass player in search of Bottesini.

Giovanni Bottesini was born into a musical family on December 22nd, 1821, in Crema, a town in Lombardy, Italy. His mother was Maria (born Spinefli) and his father, Pietro, was a local musician, a well-known claxionettist who also was interested in composition, having written several methods for various instruments. A composition of his is in Milan. His sister, Angelina, also studied music and became a fine pianist. She died in Naples in 1877.

Young Giovanni’s talent, indeed genius, for music luckily had a chance to show itself in such a musical home. He began his study of the violin at five and at the age of ten he was put in the care of his uncle, Cogliati, a priest, who was the first violinist in the orchestra of the Cathedral at Crema. He remained in this tuition for three years singing as a boy soprano, playing the drums at the Teatro Communale, continuing serious study of the Pianoforte as well as experimenting with the cello and double bass. In 1835 his father heard of two places on scholarship at the Conservatono in Milan, one for the bassoon and one for the double bass. Thus, the decision was made that was to launch Bottesini on his fantastic career. They made the journey to the big city one week ahead of the audition in order for young Giovanni to meet Professor Luigi Rossi and have some lessons prior to the big day. He impressed Rossi and the panel, and at one point in his examination made the famous remark: ‘I know, Gentlemen, that I play out of tune; but when I know where to place my fingers this shall not happen anymore.”

Here again the young man had tremendous good fortune as the school of double bass playing which existed in northern Italy at that time had already produced a series of artists who were outstanding including Langlois, Andreoli, Dal Occa, Dal Oglio and, indeed, Rossi himself. Dal Occa, for example, had been as far as St. Petersburg in Russia and back and was well-known as a soloist. It was during his stay at the conservatory that Bottesini wrote a number of compositions including the three Grand Duels and a Double Concerto with his friend, Arpesani (of whom, more later). He studied composition under Vaccaj and Basily.

Of his progress on the bass, his friend Piatti (the famous cellist with whom he was a classmate) said that after three years of study Bottesini never played better, he only gained experience! lie left the conservatory three years early with the permission of the Governors in order to do more work on composition and to begin a playing career, lie was given 300 francs on leaving and borrowed 600 more from a relative, Rachetti, using the money to buy his double bass which I will mention a bit later.

His solo debut was made in the following year (1840) in Crema (his home town) and he had tremendous success. He then undertook an extensive tour that saw him appearing in Milan “La Scala” and Vienna. The Viennese critic said of his 1840 appearance that “Giovanni Bottesini from Milan played with distinction as far as one would call the double bass a solo instrument.”

He seems to have done occasional touring as a soloist during the next six years and was engaged as last double bass in Brescia for two seasons, then as principal double bass in Verona. Verdi, who was producing I due Foscari at that theatre, heard Bottesini and advised him to follow a career as a soloist. It is said that Bottesini took on these orchestral positions in order to recover from “angina pectoris” which he is supposed to have contracted in Vienna in 1840. Neither I nor a heart specialist friend of mine think this could be true as there is no further mention of heart trouble in his life which went on for 50 more years to end with liver trouble! The heart trouble is mentioned by a contemporary biographer Cesare Lisei who was the London representative to Ricordi, wrote a brochure on Bottesini in 1884. Bottesini himself mentions his health in a letter home but in a very obscure way known only to his mother.

in 1846, Bottesini’s good friend Arditi (who was his accompanist for many years) was able to offer him a position with the opera house in Havana, Cuba, which he accepted, thus making his first of many visits to the New World.

That Company undertook tours to central America and in 1847 visited Boston, Philadelphia and New York (as well as Cape May, New Jersey, etc.) performing several operas by Verdi including Ernani, I Lombardi and I Due Foscari and also Bottesini’s first opera Cristophon Colonibo. That Company played the first Verdi ever heard in Philadelphia. Bottesini received extra money from the Company for appearances as a soloist on the bass, often during the interval of the opera. This was the beginning of a custom which he was to follow throughout his career. Even then, it seems, he was selling out the opera performances on the strength of his phenomenal abilities as a performer on the double bass. He was always very popular in North America and was made, for example, an honorary member, along with Jenny Lind, of the Philharmonic Society in New York in 1850.

Here is a letter home to his parents written in Boston, April 29, 1847.

“My most beloved father,Yesterday I had the great pleasure of receiving your very dear letter dated February 20; the consoling news of you as well as mother and Angelina’s good health have cheered me up and truly restored my peace of mind”

Part 1 - Page 2

“During this current month of April, I have been unable to write to you because I left Havana on the 3rd, which is the day when all letters to Europe must be posted. I did not arrive in New York until the 15th; the journey was very pleasant and we were treated with the highest regard. In New York, we found another Italian opera company at the Teatro Palmos, where it had been in residence for five months, and there I came across a few of our acquaintances such as Clotilde Basili, Benedette il Tenore, Sanquivrio, etc.; a man from home whose name I do not remember, is also working there as a call boy. Our managers, who were highly irritated when they discovered that the theatre was not free after all, spent 750 colommodes on another theatre in order to have the company heard in two performances of Ernani and thus, hopefully, sink the competition. Having quickly unloaded the boxes, we immediately started rehearsing until it was time to go on stage. The Park Theatre may have been minute, yet it was packed with people; we triumphed to the detriment of the others. God knows how much poison our success must have made them swallow. The next evening we played in the Sale del Tabernacolo and I performed two duets with Arditi; I am enclosing a review of the evening so that you may judge for yourself how my playing was received.

“ Before leaving Havana, I signed a new contract with the manager, engaging myself to perform in three concerts every month in exchange of which my monthly pay will be increased by 150 colommodes which will be added to the 120 I already receive as an orchestral player. I shall now be able to save a certain amount every month. You may rest assured that as soon as I am able to put together 3 or 4 thousand francs from my savings, I shall be sending them over. Please use them as seems best to you. I do not want to know about it. I shall be only too happy to find myself finally in a position to repay part of my debt towards you."

“ I spent the last five days in New York wandering about the city; having left Havana on an oppressively hot day, I was finally able to breath again—the freshness of the air here revives my lungs and pumps blood back into my veins; just like a St. Bernard dog, I start sniffing the atmosphere, it tastes of snow. I have not yet seen Paris or London but I can imagine more or less what they must be like if they at all resemble New York, for this is a great business center, highly populated, lean, elegant and hustling with activity: steam engines, railways, omnibuses, carriages, millions of newspapers. I no longer knew what world I was in."

“We then left for Boston, another very remarkable city, where Washington, the great hero to whom this country owes its freedom, preached such wholesome principles to the people. English is spoken everywhere, quite a handful for us, really, this language!"

“Everyone works for the good of the homeland, and life is quite pleasant here. There are thousands of things I could tell you, but I do not wish to deprive myself of the pleasure of relating them to you in person one day.

“We shall remain in this city until mid-May, at which point we will depart for New York where we shall be spending the summer. Before we return to Havana, we may decide to visit Philadelphia."

“I shall keep you informed at all times so that you know where to write to me. How is mother? and how is Angelina? Both well, I presume. I am surprised, though, that in the last letter my sister was not even mentioned; I assume she has left for the country with some lady. If the distance between us was not so immense, I would send her a few beautiful dresses, but that will have to wait until I get back. Tell mother that this is a country where Sundays as religious holidays are rather better observed than in our own Catholic countries; on those days, singing, playing and alcohol consumption are forbidden. Everybody goes to Church and although it is not a Catholic Church, the religion preached there is highly moral, honest and worthy of the public freedom and welfare existing in this country."

“I do remember my promise—time will tell. Don’t worry therefore, even if I suffer from not being at home; the situation has become so much of a habit that my health is not in the least affected by it. In fact, I have even become a little podgy—by my standards of course."

“I have heard nothing from my brothers. Once more, I beg of you to let me know how they are, write to me quickly and tell me what is new with them and with their wives. Have my nephews grown? I have not had the time to write to Dello. Please tell him that I received two of his letters in Havana where I also received your last two. Ask him to keep me informed on everything, and I shall do the same from here."

“When I am finished with all my engagements, I shall go on a very small trip around the U.S. and I shall then proceed towards London where I am eagerly expected. As soon as I get there I shall be sending you a modest draft so that you may come and visit me at once with mother and Angelina."

“I was very sorry to hear about Piatti’s illness in Bergomo. If you happen to see him, please send him my warmest wishes. Novelli, the bass, asks me to send you his regards, and so do Arditi and Bottoglioni, that famous Musician of Brescia."

“Our opera company is having a tremendous success. We have the inexperienced American eardrums to thank for that, for in reality it is absolutely dismal. With the exception of the Ernani, all the other operas are a disaster, horribly out of tune but always applauded! How lucky we are! I don’t know how we shall be able to cope when we are back in Italy."

“Best regards to you and please kiss mother and Angelina on my behalf. Keep well, regards to Dello. S. Angelo, Terni, Monze, all the family and friends. I remain, your affectionate and most loving son. Giovanni”

To see the famous first visit from a less personal point here is a small article about it which appeared in the MuskiIe di Milano on September 23rd of that year (1847).

“Any time the manager of the Havana theatre wishes to enlarge his capital, regardless of what part of the world he is in, all he has to do is to announce a concert or an operatic intermezzo featuring Bottesini and, in no time, he will have a hall crammed full with spectators, each of them having paid quite a hefty sum for the privilege of being there. Last July 10th, Bottesini, Arditi and the principal artists of the Italian opera, among which the great Tedesco, attracted more than 5,000 spectators to a pcrforniancc they gave in Castle Garden. They then left for Philadelphia, Boston and Cape May Island from where they shall subsequently go to Saratoga and Newport, travelling through all of the northern river area back to New York"

Part 1 - Page 3

Finally, in mid-October they shall depart for Havana. The management despatches the opera company, and notably Bottesini and Arditi, from one place to the other; those two are never allowed a moment’s rest, running from one city to the next, seeing, thanks to their work the lucky impresario who is in the process of re-engaging them, becoming richer by the minute. Sivori who, with Herz, continues to tour around America earning a fortune for himself, published on one of the pages of this periodical, a very kind declaration by way of which he expressed his great desire to meet and shake hands with the incomparable double bass player of Crema and congratulate him and the whole of Italy for the incredible success achieved everywhere. A lithograph representing both Arditi and Bottesini has just been released. The double bass player has become the object of tremendous ovations of the kind bestowed on Essler in the greatest years of her career as a solo dancer.”

1849 saw his debut in London, then as now, one of the world’s musical capitals. Both of his close school friends, Piatti and Arditi, were to settle and prosper here making enormous contributions to the musical scene. He appeared first at the Exeter Hall and his success was impossible to describe.

He was described as the “Lion of the season”; every concert series had an appearance by Bottesini. He was asked to join numerous tours both in Ireland, England and Scotland with the famous impresario and conductor Jullien who also took Bottesini as his “star” on a triumphant tour of the United States with Sir Michael Costa conducting. London seems to have been his home during large portions of his life and his residence at least in the 1850s was on Golden Square, Piccadilly.

Bottesini as the double bass player seems to have created the same reaction wherever he appeared. He usually played either his La Sonnambula fantasy or the Carnival of Venice variations for large audiences or his Grand duo Concertante together with a violinist (often with Sivori and Papini in England, Sighicelli in Paris and tours with Wieniawski, etc.). The original version of the Grand duo for double bass and violin (also listed in the musical compositions of the violinist, Sivori!!) was composed in its earliest state as a duo for two double basses for Bottesini and Arpesani to play together. The work exists under the name of Arpesani and Bottesini in various places. He wrote a great number of other compositions, most of which were used for smaller gatherings or the many specific musical evenings at which the artists of the day entertained.

Let me quote some reviews and writings from his lifetime to give us an idea of his impact as a performing artist:

“Of all the artists who have gained a reputation as players of the double bass, Bottesini is the one who possesses the greatest talent. The beauty of the tone he draws from the instrument, his marvellous dexterity and skill in conquering difficulties, his manner of making the instrument sing; the delicacy and grace of his ornaments are the component elements of a talent as complete and all-sufficing as could be desired. By his skill in producing harmonics in all positions Bottesini can compete with the most able violinists.”

“In his duet for violin and double bass, which is frequently played, he arouses the enthusiasm of his audience to the highest pitch. It is necessary to hear Bottesini in this piece to discover what possibilities are hidden in the giant of the stringed instruments; to hear what can be done in the way of sonorousness, tone, lightness of expression and grace.”

“Dragonetti, Dal Oglio, and Mueller were fine Bassists but none possess the surety of execution that makes Bottesini’s playing so brilliant."

“In precision, dash, accuracy and withal in the softness of touch and phrasing, Bottesini has no equal on the double bass.”

“Bottesini’s wonderful playing upon the unwieldy double bass is really a musical phenomenon; and those who have not heard him can have no notion of the vast resources of the double bass as a solo instrument.”

“The duo between Bottesini and Sivori was all that could be desired and we fear can never be produced save by these two artists.”

“Bottesini, who was worthily welcomed on his entrance, displayed in his double bass solo quite new powers and much other than those we should have dreamed of for this apparently unwieldy instrument. Added to its own power and breadth were sweet violin effects, only rounder and more mellow and flute-like than can be extracted from the violin. Now its harmonics were liquid and singing, and then it took the character of the violoncello, and anon growled out its bassest bass and, in the hands of this masterly performer, it eventually extended through the range and with the peculiar characteristics of three instruments.”

“An outstanding concert artist, he is called the ‘Paganini of the double bass’. Under his bow, the double bass becomes an entire orchestra with a complete range of moods.”

“Everyone was enraptured by Signor Bottesini’s solo double bass. He has the unaffected, generous, enthusiastic look of a man of genius, and no one has drawn forth more exquisite sweetness and deep-toned intense melody from the double bass than he did last night. The Duet Concertante (violin and double bass) was a rich musical treat—the full mellifluous tones of the double bass mingling and blending with the silken notes of the violin and bell like triangle chime harmonics rendered this part of the programme truly delightful.”

From these critics and many others (I hope to find still more from more diverse places) we can begin to draw a picture of how Bottesini came across. He won admiration from all for his technique and intonation but also for his musicality and ability to sing on the instrument, I have come across much mention, as well, of two other aspects of his activities which seem to escape notice, one being a fine player of chamber music.

He first played in London not as a soloist but at an evening of chamber music playing to everyone’s amazement the cello part of a quartette by Onslow. He was present playing, for another example, at the premier performance of Spohr’s Nonette. Second, he was brilliant player and accompanist on the pianoforte and seems often to have accompanied other artists on programmes where he was also engaged as soloist. Among friends, “He was amazingly versatile at the piano; he would play, sing, talk and shout, imitate the clang of the trombone, the sigh of the oboe, the trill of the flute, the roll of the drum, the crash of the cymbals! until, exhausted, he would stop improvising, push back a rebellious curl, turn to his listeners and silently question them, fixing them with a penetrating gaze that would reach their innermost thoughts.”

Part 1 - Page 4

In his concert career, Bottesini went to every corner of Europe as far as Russia (St. Petersburg), also to Turkey, and Egypt. He also went from Boston to Buenos Aires in America via Mexico and almost every country in between. Today’s soloists would be hard pressed to keep up with the travels of Bottesini. Imagine touring like that before even steamships, and surely no aeroplanes, motor cars, telephones, etc., etc. He must have spent a tremendous amount of time just travelling, and think of transporting his instrument! Fortunately, his temperament was such that he had an aversion to settling down anywhere for too long.

In his concert career, Bottesini went to every corner of Europe as far as Russia (St. Petersburg), also to Turkey, and Egypt. He also went from Boston to Buenos Aires in America via Mexico and almost every country in between. Today’s soloists would be hard pressed to keep up with the travels of Bottesini. Imagine touring like that before even steamships, and surely no aeroplanes, motor cars, telephones, etc., etc. He must have spent a tremendous amount of time just travelling, and think of transporting his instrument! Fortunately, his temperament was such that he had an aversion to settling down anywhere for too long.

Most of Bottesini’s compositions were in manuscript and not published, and, due to his constantly moving lifestyle, are well spread around. I would not be surprised if compositions continue to come light.

His compositions for the double bass are varied and, in my opinion, ingeniously constructed for the instrument. There are a number duets for double bass and other instruments (does anyone know where the Elixir of Love fantasy for double bass, cello and accomp. is?), operatic fantasies mostly on Bellini or Donizetti. (I cannot locate Lucretia Borgia), themes and variations, melodies, elegies, concertos and concerto movements. If there is a problem with his music it is a combination of solving technical difficulties combined with an understanding of the “Bel Canto” style which is now at least 100 years gone.

“. . . he is called the ‘Paganini of the double bass’. Under his bow, the double bass becomes an entire orchestra with a complete range of moods.”

He used a normal ¾ size Italian double bass tuned one tone higher or one and a half tones above the normal orchestral tuning. He used pure gut strings for all three strings and cello type (hard) resin. His bow was a slightly long French bow with white hair (although be advocates black in his Method).

His fee for a concert at which he usually played one or two numbers (Koussevitsky was the first soloist to do entire recitals and he had a number with the pianist alone included often), was in the 1860s about 500 francs. I think that must have been quite a high payment, and Bottesini earned a fortune in his lifetime being well in demand everywhere.

Bottesini’s bass belonged to the Milanese player, Fiando, and was reputed to be in a closet in a marionette theatre in that city. A friend of Bottesini, the bassist Arpesani, told him where it was. Bottesini got a prize of money from the Conservatory and borrowed the rest from a relative to buy the bass in 1839.

Contrary to popular belief, the instrument at that time had four tuners and a four string tail piece! The tuner had been removed leaving a hole in the scroll. Another hole was drilled in the centre of the tailpiece for the second string. I have heard it said that this was put lower down than the other original holes for some accoustical reason, but I doubt that. This was a simple conversion from four to three strings!

Bottesini felt strongly in favour of three strings of pure gut in time when some places in the 1840s used, traditionally, four and even five strings, such as Germany. France had just accepted the four stringed instrument as standard at the Conservatoire, and Italy, England, Spain, etc. were still using three strings as standard (I saw a three-stringed instrument in Spain last month). I suppose England was one of the last places to change over, as three strings were rather common here until the first war. There was also a controversy pro and con about the metal wrapped bottom strings going on at that time among all the bass players.

The instrument was made in 1716 by Carlo Antonio Testore in Milan, the eldest son of Carlo Giuseppe. It is very typical of this maker. I have seen several which are almost identical to the Bottesini bass. I have read that it was by Carlo Giuseppe, but this is not true. The instrument was made with the flat back and ribs of pearwood which was popular with the makers in the north of Italy for basses and cellos (along with poplar and a type of willow). The instruments from thismaterial almost always have the traditional cherry-brown colour and this one is no exception. The Testore family seemed to have a great selection of beautiful pine and the table of this instrument is a good example. The ff holes slant inwards toward the bottom and are typical of the maker. The table length is 45¼”, 19¼” across at the upper bouts, and 25 5/8” across the lower part, the depth in the rib being 8” at the bottom. These measurements refute the misconception that the bass was a “Basso da Camera” or of small size.

The instrument is the normal ¾ size Italian Contrabbasso in every respect. On Bottesini’s death, the instrument was passed on to an advocate in Torino for settlement of his estate and was subsequently sold to Hill and Sons, the London dealers. The bass was then bought by Claude Hobday, the famous English Bassist, in 1894. At that time the instrument was converted to four strings, keeping the existing tailpiece but losing the original three tuners, replacing them with the English type and making the string length the modern norm of just under 42” and having a “d” stop. Previously the stop had been nearer Eb and the string length closer to 44”. The longer neck would, of course, have made several significant differences for Bottesini. First the sound would have been bigger and brighter owing to the longer string. Secondly, as Bottesini played semi-tones in the lower register 1-4 (the “Scuola Lombardo”), the longer string would have been more comfortable! Thirdly, the harmonics and upper register would have been easier to reach, as the shoulders are not too sloping on this instrument.

Part 1 - Page 5

I believe that the bass bar was changed at the same time. The work was done, I believe, by Hill and Son who certified the instrument as well at that time. The instrument during Bottesini’s ownership had a slightly raised bottom nut which may have been there when he bought it but was surely there from the 1860s onwards through Hobday’s ownership. When Claude Hobday died, the instrument was purchased by James Merrett Sr., the well-known London player and teacher, and on his death the instrument was left to his son, James Jr. It was at this time that I came to know the instrument. (1 replaced James Jr. as professor at the Guildhall School of Music, London.) When James Jr. died in 1974, the instrument was offered for sale for 3,500.00 Pounds and the wish was expressed that it not leave England. An instrument dealer, a Mr. Duffy, purchased the instrument, and I understand that it is now in Japan!

I believe that the bass bar was changed at the same time. The work was done, I believe, by Hill and Son who certified the instrument as well at that time. The instrument during Bottesini’s ownership had a slightly raised bottom nut which may have been there when he bought it but was surely there from the 1860s onwards through Hobday’s ownership. When Claude Hobday died, the instrument was purchased by James Merrett Sr., the well-known London player and teacher, and on his death the instrument was left to his son, James Jr. It was at this time that I came to know the instrument. (1 replaced James Jr. as professor at the Guildhall School of Music, London.) When James Jr. died in 1974, the instrument was offered for sale for 3,500.00 Pounds and the wish was expressed that it not leave England. An instrument dealer, a Mr. Duffy, purchased the instrument, and I understand that it is now in Japan!

According to my colleague, Adrian Beers, who was certainly the finest pupil of Hobday, the box for the bass, which was literally covered with exotic luggage labels and stickers from all over the world, was left to disintegrate behind the Royal College of Music. At least we are left the instrument, hopefully to survive us all into history. Bottesini admired most the instruments of Gasparo da Salo though he wouldn’t have selected an instrument of such a grand pattern as a solo instrument, and owned a number of instruments at various times including another Testore, I understand. The 1716 instrument, however, was his constant companion throughout his playingcareer. Considering the traveling that Bottesini did, I’m amazed to say that, when I knew the instrument, it was in very good condition. It might also be interesting to mention that, while there have been attempts over the years, Herr Horst Grunert of Penzberg, W. Germany has succeeded, to my mind, at producing a copy of the instrument which is superb in every respect. The tone is magnificent and the material and workmanship beyond fault. The varnish is the traditional one in oil. In my opinion Grunert will emerge in the future as one of the most important makers of basses.

Bottesini’s instrument, in addition to the normal and genuine label dated 1716, has several repair records inside, one from Madrid in 1871 and another from Buenos Aires in 1879 (the date of the production of Ero & Leandro there).

END OF PART ONE

Thomas Martin studied the Double Bass in America under Harold Roberts and Roger Scott. He has held principal positions with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Montreal Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, and Academy of St. Martin—in the Fields. He is now the co-principal with the English Chamber Orchestra.

Thomas Martin has been made fellow of the Guildhall School of Music in London, where he has been Professor of Double Bass for some years. A frequent visito to Ireland, he gives a series of popular Master classes each year for the Dublin Philharmonic Society. In addition, he has just released a new all-Bottesini album see “New Releases”.

Part 2 - Page 6

GIOVANNI BOTTESINI THOUGHT of himself as a composer who played the double bass. It is one of the cruel paradoxes of musical history that the goal which he wanted most to achieve continually eluded him. One of his contemporary biographers writing about his later life said, “Tired of touring, it seems that Bottesini wants to dedicate his noble gift and all the treasures of his noble doctrine almost exclusively to the Opera Theatre where, despite the success of his previous operas, it has to be admitted that he has not been able to make the sort of impact that takes a composer to the forefront and assures his popularity. So far he has written worthy scores, admired and appreciated by the intellectuals, but he has yet to write a score that would excite the public, that great and just dispenser of applause and censure. Some maintain he lacks inspiration, the high and powerful inspiration that alone creates master pieces and this may be true as it also may be that he is finally in these last years about to capture that feeling of inspiration.

GIOVANNI BOTTESINI THOUGHT of himself as a composer who played the double bass. It is one of the cruel paradoxes of musical history that the goal which he wanted most to achieve continually eluded him. One of his contemporary biographers writing about his later life said, “Tired of touring, it seems that Bottesini wants to dedicate his noble gift and all the treasures of his noble doctrine almost exclusively to the Opera Theatre where, despite the success of his previous operas, it has to be admitted that he has not been able to make the sort of impact that takes a composer to the forefront and assures his popularity. So far he has written worthy scores, admired and appreciated by the intellectuals, but he has yet to write a score that would excite the public, that great and just dispenser of applause and censure. Some maintain he lacks inspiration, the high and powerful inspiration that alone creates master pieces and this may be true as it also may be that he is finally in these last years about to capture that feeling of inspiration.

Of course he loved his instrument which brought him to the forefront of all the musicians of his time; that success, however, was at the expense of his composition. His financial situation, as well, was such that at many times, particularly in later life when he would have liked nothing better than to settle down in order to devote himself to composition, he was forced to undertake concert tours with his great friend and breadwinner, the Double Base, in order to keep the wolf from the door. For this reason, it seems his life was a somewhat frustrated one.

That frustration showed itself early in his life, for he left Conservatory in Milan three years early (with the blessing of the governors) in 1939 in order to “give himself up to composition in a freer atmosphere” as he felt drawn to it. His teachers were Piantanida Ray, Basili and Vaccai. One contemporary summed his compositional aim by saying. “His sympathies favour the beautiful school for Italian melody enriched by the modern art of orchestration. To him, Rossini’s William Tell and Gounod’s Faust are standards of Beauty and the realization of his ideal of musical loveliness, he is really a cosmopolitan in taste and unreservedly admits the merits of composers whose music differs in all essentials from his.”

Bottesini had completed quite a large number of compositions by the time of is London debut in 1849. At Conservatory in Milan he had undertaken such daunting assignments as a quartet for harps, not to mention string quartets. Almost all of his famous compositions for the double bass were written in one form or another by that time, ad he had already completed his first opera: “Cristoforo Colombo” was written in Havana (Teatro Tacon 1847), in two acts with the libretto in Spanish.

Bottesini’s first major operatic undertaking was L’assedio di Firenze (Siege of Florence), which was given its first performace in Paris at the Theatre des Italiens on 2 Feb 1856, and was repeated at La Scala (1860), among other places. A Viennese critic who commented on the Paris performance said that the opera was very well received and was thought to be very good. He felt that the writing for the orchestra was excellent but the writing the voices was not up to the same standard, remarking that Bottesini was far better at singin on his instrument. The critic mentioned that Bottesini played his “Carnival of Venice” in the interval, as was custom, and said it was a pity that the audience was compelled to cry out so much during the performance.

His next opera was written in 1858 and called “Il Diavalo della Notte”. It was know that the full score to this opera, as well as L’assedio di Firenze still exists. 1862 found him composing the first of his three best-known and best received operas, Marion Delorme. It was written on a libretto by Ghislanzoni (who wrote Aida, among other libretti) based on a novel by Victor Hugo. The performance was in Palermo (Jan 10). It was repeated in 1864 in Barcelona, where Bottesini was given a silver baton by the chorus and a silver crown by the orchestra of the Liceo Theatre engraved “to the worthy Professor Sr. Juan Bottesini, a tribute of friendship, wonder, and respect.” The absolutely glowing review went on for pages, and excerpts from which gives us an idea of where Bottesini stood at that time in musical history:

“Now, when the world feels the destruction of its true Italian school due to the wrongly called Verdian style that has destroyed not only the beautiful and pure melodies which formed its glory, and when we see with amazement the slovenliness in which the Italian school has fallen as well as its old and celebrated Conservatories, we heard with amazement, we say again, Maria Delmore by Bottesini, because the melodies it contains are original, pure and simple as Bellini’s, having a spiritual sound so marvellous that it makes us be in paradise. We have also heard it with wonder, because every bit of it fits in its place together with an excellent orchestration. We do not know what to praise more in Bottesini, his melodic and compound genius, or his philosophical talent to develop the drama musically, or the knowledge he has in the fields of orchestration and composition.

“All the things can be seen in his work which is developed with easiness, simplicity, and loftiness.”

The full score of this opera exists, but the exact location is not known. The libretto and stage movements, however, have been found.

Bottesini appeared as soloist at the Casino in Monte Carlo in 1864. At a theatre nearby was a fine troupe of singers from Paris, for whom he wrote a one-act opera called Vinciguerra, Il bandito. They performed it in Monte Carlo and subsequently took it to Paris for forty consecutive performances.

Part 2 - Page 7

Next came the second of his great operatic successes, Ali Baba, his great comic opera. Ali Baba, in four acts, was written and first performed in London at the Lyceum Theatre in 1870. Bottesini was acting as conductor for the season, as he had been forced to flee Paris owing to the advance of German troops on that city. Ali Baba was a great success and had a long and appreciated run. Only the piano score to this opera, is known but it is believed that the full score exists.

Next came the second of his great operatic successes, Ali Baba, his great comic opera. Ali Baba, in four acts, was written and first performed in London at the Lyceum Theatre in 1870. Bottesini was acting as conductor for the season, as he had been forced to flee Paris owing to the advance of German troops on that city. Ali Baba was a great success and had a long and appreciated run. Only the piano score to this opera, is known but it is believed that the full score exists.

Bottesini’s great opera is “Ero e Leondro” (Hero and Leander) which was composed during his tenure as director of the Italian Opera in Cairo in 1875 at a villa near Ramle outside Cairo. The libretto was by Boito, who was Verdi’s chief librettist and a good composer in his own right (Mefistofile). The first performance took place in Torino with a fabulous cast in 1879. It was repeated 20 times that season to ovations. The Director of the Teatro Reggio, who mounted this first performance stated:

“That Boito should have renounced the idea of setting Ero e Leandro to music himself is a great shame, considering the fourth act of Mefistofile. It is also amazing that Bottesini should have chosen this libretto to compose an opera on; and yet he was successful with this as with a few others, and Ero was his greatest success in serious opera as Ali Baba was in comic opera.

“If his virtuosity made him a famous concert artist, it was at the expense of composing. In Bottesini inventive originality did not correspond to spontaneity; technically skilled and a capable instrumentalist, he more often than not proved unequal to the task of composition. The impatience of the concert artist was revealed in obvious improvisations which were merely concessions to the dubious taste of his audience. Having decided to become a composer, he had neither the patience nor the desire to really work at it; it was enough for him that his work sparkled, was applauded, and he could move on to other things.

“Bottesini can be regarded as one of the last exponents of the Italian school that was bound to the traditions of Bellini and Donizetti. He was a confirmed enemy of the Wagnerian revolution; he was even ready to set to music a satire against the Wagnerians, of which I have read the libretto. In later years he spoke out strongly against all those he held responsible for all that was bad in the Italian theatre. Accusing others of intolerance, he passed into even worse intransigence. The classical form of the Italian opera he considered sacred, and he really believed that he could bring it up to date by working on the counterpoint and orchestration. Such a view reduced the Italianness to a question of style and obscured the content.

“In choosing his libretti he also followed the old school and did not go for subtlety. He would use any libretto he came across—and he came across some very unfortunate ones—and, suffering somewhat from a persecution complex, he blamed his editors, impressarios and colleagues for what was partly the result of his poor choice of libretto and partly his excessive indulgence for his creations, namely the lukewarm success of some of his scores and difficulties over mounting them.

“I do remember my promise—time will tell. Don’t worry therefore, even if I suffer from not being at home; the situation has become so much of a habit that my health is not in the least affected by it. In fact, I have even become a little podgy—by my standards of course."

“I have heard nothing from my brothers. Once more, I beg of you to let me know how they are, write to me quickly and tell me what is new with them and with their wives. Have my nephews grown? I have not had the time to write to Dello. Please tell him that I received two of his letters in Havana where I also received your last two. Ask him to keep me informed on everything, and I shall do the same from here."

“When I am finished with all my engagements, I shall go on a very small trip around the U.S. and I shall then proceed towards London where I am eagerly expected. As soon as I get there I shall be sending you a modest draft so that you may come and visit me at once with mother and Angelina."

“I was very sorry to hear about Piatti’s illness in Bergomo. If you happen to see him, please send him my warmest wishes. Novelli, the bass, asks me to send you his regards, and so do Arditi and Bottoglioni, that famous Musician of Brescia."

“Our opera company is having a tremendous success. We have the inexperienced American eardrums to thank for that, for in reality it is absolutely dismal. With the exception of the Ernani, all the other operas are a disaster, horribly out of tune but always applauded! How lucky we are! I don’t know how we shall be able to cope when we are back in Italy."

“Best regards to you and please kiss mother and Angelina on my behalf. Keep well, regards to Dello. S. Angelo, Terni, Monze, all the family and friends. I remain, your affectionate and most loving son. Giovanni”

To see the famous first visit from a less personal point here is a small article about it which appeared in the MuskiIe di Milano on September 23rd of that year (1847).

“Any time the manager of the Havana theatre wishes to enlarge his capital, regardless of what part of the world he is in, all he has to do is to announce a concert or an operatic intermezzo featuring Bottesini and, in no time, he will have a hall crammed full with spectators, each of them having paid quite a hefty sum for the privilege of being there. Last July 10th, Bottesini, Arditi and the principal artists of the Italian opera, among which the great Tedesco, attracted more than 5,000 spectators to a pcrforniancc they gave in Castle Garden. They then left for Philadelphia, Boston and Cape May Island from where they shall subsequently go to Saratoga and Newport, travelling through all of the northern river area back to New York"

Part 2 - Page 8

“As the logical result of his concept of melodrama, Bottesini only looked for and found ‘episodes’ in his libretti; he gave little importance to a logical development of plot or characterization. This restricted view denied him the ability to create great works of art. In fact, in Ero e Leandro we find exquisite pieces of composition followed by pieces that are frankly vulgar, which would seem inexplicable if we were to ignore the indifference of composers of Bottesini’s school to everything they considered mere accessories of no importance to the opera.

“But even so, every now and then Bottesini’s poetic sentiments flowed bright and pure from his imagination. Limiting myself to Ero e Leandro, I must say that the religious entreaty in the first act, Leandro’s declaration, the drinking song, various extracts from the two love duets and the Barcarole are totally appropriate. The depiction of a moonlight night on the Bosporus which opens the third act is truly exquisite. A few minor changes, and the evocation would be perfect; the spirit of the scene reveals itself, and we are filled with the sound of the orchestra and the muted voices of the chorus so that we are lost in the blue of sea and sky.

“Ero e Leandro, an opera created during every sort of vexation and worry, provided in exchange Bottesini’s last joys. Acquired by Ricordi, it was performed for many years in the major opera houses in Italy, Europe and South America, until it was superseded by the Ero e Leandro of Luigi Mancinelli written on the same libretto. Mancinelli was conducting the Bottesini opera in Rome and fell in love with the story. As Bottesini had never bothered to secure the literary copyright, Mancinelli set it to music as well.

“I recall that during one of the first performances of the opera, at universal insistence, Bottesini gave a recital between acts. The crowd that accumulated was so great that the management had to stop the sale of tickets half an hour before the performance was to begin. Bottesini left Torino in triumph, having been commissioned to write a new opera.”

THAT OPERA, La Regina di Nepal, was not well-received, and reinforced the views of the previously quoted theater director, who was the man who produced both operas and commissioned the second. The opera was damaged by a last-minute change of the leading tenor, and one is given to understand that this may well have ruined the performance. Here is the backstage description by another contemporary who was there at the time:

“The tenor became the scapegoat of the evening. It was as if the enthusiasm aroused by Ero e Leandro had been totally obliterated; the Regina di Nepal could just as easily have been the work of any insignificant composer, judging by the sulkiness of the audience. When the first-act curtain came down, there was utter silence! Oh, that silence!

“He who is not familiar with the backstage world cannot imagine the torture the poor composer is subjected to when he sees the curtain slowly coming down and hears no applause, no whistling, nothing, only a vague indistinct rustling seemingly miles away; yet this rustling is like a hammer on his temples, a knife in his heart already pricked by a thousand needles. He then wishes for the cries, the hisses, the shouts of a furious audience rather than that deadly silence.

“During the second act, still the same menacing silence; the electricity in the atmosphere weighed upon all his friends, and the interval seemed endless. Bottesini affected to be calm, but the glare in his eyes betrayed deep agitation. Retreating in the artists’ passageway behind the stage, he paced up and down, his head hanging low, his shoulders bent, his hands thrust in the pockets of his unbuttoned jacket. From time to time he stopped, listened, and almost immediately, fearing he would hear something, resumed his pacing up and down the corridor. He uttered not a word; what could he have said? We did not address him; what would we have dared say? During one of his pauses, a clamour made him start. He tossed his head, smiled bitterly, and said, ‘It’s finished!’

The clamour continued with increasing intensity. Suspecting some public uprising against his work, he prepared to flee from the theatre; but at that moment the announcer, the choir master and various other people came running towards him, shouting: ‘Maestro, Maestro! On stage, on stage!’ Bottesini turned pale; he was as white as a corpse. Turollo and Battistini, who with their interpretation of the second-act duet had moved the audience to tears, dragged the Maestro, pale and tense, on stage. When he returned back stage, he tossed his hat onto the floor, and leaning against the wall, in spite of his great resistance to the upheavals of theatre life, he who had been acclaimed all over the world for his performances on the double bass, burst into tears. He had been able to control himself in the face of so much public indifference, but when the audience started applauding, he, in one of those sudden reactions which often accompany downfalls, broke down completely. The image of that tall, virile figure prostrated and sobbing against the wall in the confusion of a first performance has remained engraved in my memory; thirty years have gone by, and I have not forgotten, and, indeed, I shall never forget.”

Despite this disastrous first performance, Regina di Nepal went on to run for 15 performances, attracting more and more interest and acclaim as it went on, eventually making a good profit or the theatre.

IN ADDITION TO the operas already mentioned, more were left unpublished, all written in his last years. He offered two for performance to the same Teatro Reggio in Torino in a letter to the Director in 1881. Three more were written in London about the time of his oratorio, all of them in three months 1886-87. These operas were: La torre di Babele, La figlia dell ‘Angelo, Azaele, Cedar, and Graziella.

The Teatro Reggio in Torino also was the scene of the first performance (in 1880-81) of a work Bottesini considered to be one of his finest compositions, his Missa da Requiem for four solo voices. chorus, and orchestra. This work was also chosen by his home town of Crema to represent them in the great musical exposition of 1881 in Milan, where it was awarded the gold medal. It is believed that there is a full score of this work in London.

Part 2 - Page 9

GIOVANNI BOTTESINI THOUGHT of himself as a composer who played the double bass. It is one of the cruel paradoxes of musical history that the goal which he wanted most to achieve continually eluded him. One of his contemporary biographers writing about his later life said, “Tired of touring, it seems that Bottesini wants to dedicate his noble gift and all the treasures of his noble doctrine almost exclusively to the Opera Theatre where, despite the success of his previous operas, it has to be admitted that he has not been able to make the sort of impact that takes a composer to the forefront and assures his popularity. So far he has written worthy scores, admired and appreciated by the intellectuals, but he has yet to write a score that would excite the public, that great and just dispenser of applause and censure. Some maintain he lacks inspiration, the high and powerful inspiration that alone creates master pieces and this may be true as it also may be that he is finally in these last years about to capture that feeling of inspiration.

GIOVANNI BOTTESINI THOUGHT of himself as a composer who played the double bass. It is one of the cruel paradoxes of musical history that the goal which he wanted most to achieve continually eluded him. One of his contemporary biographers writing about his later life said, “Tired of touring, it seems that Bottesini wants to dedicate his noble gift and all the treasures of his noble doctrine almost exclusively to the Opera Theatre where, despite the success of his previous operas, it has to be admitted that he has not been able to make the sort of impact that takes a composer to the forefront and assures his popularity. So far he has written worthy scores, admired and appreciated by the intellectuals, but he has yet to write a score that would excite the public, that great and just dispenser of applause and censure. Some maintain he lacks inspiration, the high and powerful inspiration that alone creates master pieces and this may be true as it also may be that he is finally in these last years about to capture that feeling of inspiration.

Of course he loved his instrument which brought him to the forefront of all the musicians of his time; that success, however, was at the expense of his composition. His financial situation, as well, was such that at many times, particularly in later life when he would have liked nothing better than to settle down in order to devote himself to composition, he was forced to undertake concert tours with his great friend and breadwinner, the Double Base, in order to keep the wolf from the door. For this reason, it seems his life was a somewhat frustrated one.

That frustration showed itself early in his life, for he left Conservatory in Milan three years early (with the blessing of the governors) in 1939 in order to “give himself up to composition in a freer atmosphere” as he felt drawn to it. His teachers were Piantanida Ray, Basili and Vaccai. One contemporary summed his compositional aim by saying. “His sympathies favour the beautiful school for Italian melody enriched by the modern art of orchestration. To him, Rossini’s William Tell and Gounod’s Faust are standards of Beauty and the realization of his ideal of musical loveliness, he is really a cosmopolitan in taste and unreservedly admits the merits of composers whose music differs in all essentials from his.”

Bottesini had completed quite a large number of compositions by the time of is London debut in 1849. At Conservatory in Milan he had undertaken such daunting assignments as a quartet for harps, not to mention string quartets. Almost all of his famous compositions for the double bass were written in one form or another by that time, ad he had already completed his first opera: “Cristoforo Colombo” was written in Havana (Teatro Tacon 1847), in two acts with the libretto in Spanish.

Bottesini’s first major operatic undertaking was L’assedio di Firenze (Siege of Florence), which was given its first performace in Paris at the Theatre des Italiens on 2 Feb 1856, and was repeated at La Scala (1860), among other places. A Viennese critic who commented on the Paris performance said that the opera was very well received and was thought to be very good. He felt that the writing for the orchestra was excellent but the writing the voices was not up to the same standard, remarking that Bottesini was far better at singin on his instrument. The critic mentioned that Bottesini played his “Carnival of Venice” in the interval, as was custom, and said it was a pity that the audience was compelled to cry out so much during the performance.

His next opera was written in 1858 and called “Il Diavalo della Notte”. It was know that the full score to this opera, as well as L’assedio di Firenze still exists. 1862 found him composing the first of his three best-known and best received operas, Marion Delorme. It was written on a libretto by Ghislanzoni (who wrote Aida, among other libretti) based on a novel by Victor Hugo. The performance was in Palermo (Jan 10). It was repeated in 1864 in Barcelona, where Bottesini was given a silver baton by the chorus and a silver crown by the orchestra of the Liceo Theatre engraved “to the worthy Professor Sr. Juan Bottesini, a tribute of friendship, wonder, and respect.” The absolutely glowing review went on for pages, and excerpts from which gives us an idea of where Bottesini stood at that time in musical history:

“Now, when the world feels the destruction of its true Italian school due to the wrongly called Verdian style that has destroyed not only the beautiful and pure melodies which formed its glory, and when we see with amazement the slovenliness in which the Italian school has fallen as well as its old and celebrated Conservatories, we heard with amazement, we say again, Maria Delmore by Bottesini, because the melodies it contains are original, pure and simple as Bellini’s, having a spiritual sound so marvellous that it makes us be in paradise. We have also heard it with wonder, because every bit of it fits in its place together with an excellent orchestration. We do not know what to praise more in Bottesini, his melodic and compound genius, or his philosophical talent to develop the drama musically, or the knowledge he has in the fields of orchestration and composition.

“All the things can be seen in his work which is developed with easiness, simplicity, and loftiness.”

The full score of this opera exists, but the exact location is not known. The libretto and stage movements, however, have been found.

Bottesini appeared as soloist at the Casino in Monte Carlo in 1864. At a theatre nearby was a fine troupe of singers from Paris, for whom he wrote a one-act opera called Vinciguerra, Il bandito. They performed it in Monte Carlo and subsequently took it to Paris for forty consecutive performances.

Part 3 - Page 10

In tracing Giovanni Bottesini’s movements as a conductor, they are nearly impossible to separate from his movements as a soloist, as he frequently appeared in both capacities, in addition to (as mentioned in Part two) trying to find time for his great love, composition.

In tracing Giovanni Bottesini’s movements as a conductor, they are nearly impossible to separate from his movements as a soloist, as he frequently appeared in both capacities, in addition to (as mentioned in Part two) trying to find time for his great love, composition.

As a musician in this period of Music History, Bottesini had “seasons” of Opera or concerts lasting a matter of weeks to months in one place, and long “tours” in which a group of artists went from town to town appearing in the “pot pourri” type of mixed concerts which were popular at that time, each appearing in several numbers and often accompanying each other.

Bottesini’s career as a conductor probably began during his days at the Milan Conservatory, and blossomed during his stay at the Teatro Tacon in Havana. He went to Havana in 1846 with his great friend, Luigi Arditi, the leading violinist and conductor. Bottesini was principal double bass and “Maestro al piano”, which un-doubtedly included some conducting. Also, he was involved in conducting his first operatic venture, Christopher Columbus, (although the actual title was Colon en Cuba (Columbus in Cuba).

Arditi recalled this period fondly in his reminiscences, saying that he and Bottesini shared a quaint house with large windows with “innumerable parrotts (sic) and dogs” (not Bottesini’s last collection of animals.) Apparently, they had a servant named Francesco who Bottesini, though far from rich, was continually bailing out of jail for being out after curfew.

Arditi wrote a number of compositions for this partnership which had begun earlier in Italy. (Arditi, Bottesini, and their other friend Piatti had all appeared together in numerous concerts, including the coronation of Emperor Ferdinand in Vienna where they were “enthusiastically applauded by the Austrian court”). His works included a fantasia on I Puritani for violin and double bass, a Carnival of Venice Fantasy for the same combination as well as a Scherzo on Cuban Melodies. Bottesini also was busy composing during this time. Some of his compositions from Cuba include: Music for the poem Dia Nebuloso, a Birthday Ode to Isabel II, and a Nocturne for violin and piano.

It seems that Bottesini was terribly sea sick all the way from Genoa to Havana, not surprising when one considers that he was sailing before steam ships! Given this fact, plus his fear of carriages, it is surprising that he became such a perpetual traveller. Once arrived in Cuba and having recovered, he was taken to everyone’s heart and was known as Juan Bottesini.

On his first visit to England in 1848, he appeared as a conductor at the music festivals in Buckingham and Birmingham. By the time of his debut concert as a soloist in London, the Times mentioned that “The Italian artistes (sic) who have been associated with Bottesini speak in the most enthusiastic terms of his abilities as a music director and conductor of an orchestra”.

He was, during this period, at the height of his career as a soloist. He did not have an official post as a conductor until 1853 in Mexico at the Teatro Santanna. There he helped to organize the Conservatory of Music, and was engaged as music director of the Opera by the great soprano of the day, Henrietta Sontag (the Countess Rossi), who died the following season in Bottesini’s presence. He returned to Havana in 1855, and then in 1856 the post of Musical.

Director was offered him by the Theatre des Italiennes in Paris. This was a highly prestigious post having had previous directors such as the great Rossini himself.

Bottesini used these opportunities as Musical Director to secure the performance of his compositions, and thus the premier of the Siege of Florence in Pans in 1856. Soon after his arrival in Paris he was invited to the Tuilleries to perform before Napoleon the Ill had heard of the great success that greeted the concert-artist wherever he went. He was duly received in the ante chamber to the concert room by the grand master of ceremonies, Count Bacciocchi; who asked him hundreds of questions about his instrument: how it was made, its size, harmonic qualities etc.. All of this left Bottesini bemused until the question was asked “and is it empty or full. Maestro?” At this. Bottesini almost burst out laughing until he remembered the recent attempt on the Emperor’s life by Felice Orsini. Controlling himself in time, he solemnly answered “Empty, empty, sir!” Needless to say, he had the warmest applause at the court and this only served to bring him further to the attention of the public of Paris.

He alternated with Berlioz in conducting the formidable army of distinguished musicians which had been especially put together for the great ‘Exposition Universelle’ in Paris. He was awarded a silver medal by the Paris Conservatory in the presence of many dignitaries and made many successful appearances all over France and Europe. Bottesini anticipated a stay in Paris of about seven years.

The next year, however, he set off on what turned out to be a constant tour which lasted from 1857 to 1861, mostly appearing as a soloist with some conducting and accompanying. He visited Germany, Holland. Belgium, and France; paid his annual visits to England: toured Portugal and Italy extensively (1858); and in 1859 made a French tour as conductor and soloist. One opera was produced during this period Il diavolo della notte (Milan 1859) which is thought to be one of his finest. 1860 included a long tour of almost every city in England and Ireland with Sivori the violinist and the soprano Signora Fiorentini.

From 1861 through 1863, Bottesini took a post as Music Director of the Teatro Bellini in Palermo, but still found time for extensive tours as far as Dublin again. His opera Marion Delorme was produced (the leading soprano: Signora. Fiorentini) in Palermo in 1862. In 1863 the recently opened Liceum Theatre in Barcelona engaged both Bottesini as their Music Director which he accepted until mid-1866, combining that post with a series in Monaco. Maria Delorme, (as they called it) received an enthusiastic run in Barcelona as well, with the same soprano as in Palermo, Signora Fiorentini! She had at that time, been contracted to sing at the Italian Opera in Paris, the Queens Theatre in London, La Scala in Milan, as well as Mexico, Havana, Berlin, Dresden, Florence, Palermo, and Nice. (Claudine Florentine Williams, who was called Signora Fiorentini, was a close friend of Bottesini.

She toured with him in his early years; “Maria Delorme” was written for her, and she performed it both in Palermo and Barcelona and perhaps other places. Baptie claims that Bottesini married her in 1878. There is, however, no record of this.)

Bottesini’s tours went as far as England each year and in 1866 (one of his busiest years) he set off for tours of the U.S.A. and Cuba, was named Musical Director of the popular “Buen Retiro” concerts in Madrid, appeared in the promenade seasons and Arditi’s concerts etc. in London, and went on an extended tour (December 1866 through March 1867) of Russia under the direction of Anton Rubenstein. He returned from Russia to Pails from where he set out on a monster tour of provincial France as well as all of Scandinavia with Vieuxtemps. He then returned to London where he had been appointed Musical Director of the popular Promenade concert season at Covent Garden, where the “Conductor of the Dance Music” appearing with him was none other than Johann Strauss! In 1869 Bottesini toured France with Vieuxtemps again and the harpist Godefroid, with a program which began with Bottesini conducting Rossini’s Missa Solemnis.

Advancing German forces in the Franco-Prussian war brought Bottesini to London for an unexpected stay. He spent the last six weeks of the year and early 1870 writing his comic opera Ali Baba which was given as part of the season of opera at the Lyceum Theatre, London, where he was the Musical Director. At the same time he was Music Director of the Covent Garden Prom. season.

Broneth Bay, Director of the Italian Opera at the Kadivale Theatre in Cairo, met Bottesini in London in 1870 and engaged him on a long-term contract as their Musical Director. He held this post (as well as the Italian Opera in Constantinople which he added in 1873), until the Cairo Opera closed down in 1879. Bottesini managed during his Cairo years to go off on tours to Spain and Portugal, and even directed the Lyceum season in London.

In 1871 the premiere of Verdi’s opera Aida took place in Cairo, having been postponed a year due to the Franco-Prussian war. When Verdi’s favourite conductor (Mariani) was too ill to conduct, the important task fell on the worthy shoulders of Bottesini. The performances took place as part of the opening ceremonies for the Suez Canal and Bottesini was able to fit in a three day visit with Verdi at Saint ‘Agata in order to study the score. Much correspondence took place between Verdi and Bottesini. The first performance took place on December 24 to a crowd made up of the highest ranking dignitaries from most of the countries of the world, critics of all nationalities, as well as an enormous cosmopolitan crowd of spectators, all of whom greeted the work with enormous enthusiasm.

Part 3 - Page 11

He alternated with Berlioz in conducting the formidable army of distinguished musicians which had been especially put together for the great ‘Exposition Universelle’ in Paris. He was awarded a silver medal by the Paris Conservatory in the presence of many dignitaries and made many successful appearances all over France and Europe. Bottesini anticipated a stay in Paris of about seven years.

He alternated with Berlioz in conducting the formidable army of distinguished musicians which had been especially put together for the great ‘Exposition Universelle’ in Paris. He was awarded a silver medal by the Paris Conservatory in the presence of many dignitaries and made many successful appearances all over France and Europe. Bottesini anticipated a stay in Paris of about seven years.

The next year, however, he set off on what turned out to be a constant tour which lasted from 1857 to 1861, mostly appearing as a soloist with some conducting and accompanying. He visited Germany, Holland. Belgium, and France; paid his annual visits to England: toured Portugal and Italy extensively (1858); and in 1859 made a French tour as conductor and soloist. One opera was produced during this period Il diavolo della notte (Milan 1859) which is thought to be one of his finest. 1860 included a long tour of almost every city in England and Ireland with Sivori the violinist and the soprano Signora Fiorentini.

From 1861 through 1863, Bottesini took a post as Music Director of the Teatro Bellini in Palermo, but still found time for extensive tours as far as Dublin again. His opera Marion Delorme was produced (the leading soprano: Signora. Fiorentini) in Palermo in 1862. In 1863 the recently opened Liceum Theatre in Barcelona engaged both Bottesini as their Music Director which he accepted until mid-1866, combining that post with a series in Monaco. Maria Delorme, (as they called it) received an enthusiastic run in Barcelona as well, with the same soprano as in Palermo, Signora Fiorentini! She had at that time, been contracted to sing at the Italian Opera in Paris, the Queens Theatre in London, La Scala in Milan, as well as Mexico, Havana, Berlin, Dresden, Florence, Palermo, and Nice. (Claudine Florentine Williams, who was called Signora Fiorentini, was a close friend of Bottesini.

She toured with him in his early years; “Maria Delorme” was written for her, and she performed it both in Palermo and Barcelona and perhaps other places. Baptie claims that Bottesini married her in 1878. There is, however, no record of this.)

Bottesini’s tours went as far as England each year and in 1866 (one of his busiest years) he set off for tours of the U.S.A. and Cuba, was named Musical Director of the popular “Buen Retiro” concerts in Madrid, appeared in the promenade seasons and Arditi’s concerts etc. in London, and went on an extended tour (December 1866 through March 1867) of Russia under the direction of Anton Rubenstein. He returned from Russia to Pails from where he set out on a monster tour of provincial France as well as all of Scandinavia with Vieuxtemps. He then returned to London where he had been appointed Musical Director of the popular Promenade concert season at Covent Garden, where the “Conductor of the Dance Music” appearing with him was none other than Johann Strauss! In 1869 Bottesini toured France with Vieuxtemps again and the harpist Godefroid, with a program which began with Bottesini conducting Rossini’s Missa Solemnis.

Advancing German forces in the Franco-Prussian war brought Bottesini to London for an unexpected stay. He spent the last six weeks of the year and early 1870 writing his comic opera Ali Baba which was given as part of the season of opera at the Lyceum Theatre, London, where he was the Musical Director. At the same time he was Music Director of the Covent Garden Prom. season.

Broneth Bay, Director of the Italian Opera at the Kadivale Theatre in Cairo, met Bottesini in London in 1870 and engaged him on a long-term contract as their Musical Director. He held this post (as well as the Italian Opera in Constantinople which he added in 1873), until the Cairo Opera closed down in 1879. Bottesini managed during his Cairo years to go off on tours to Spain and Portugal, and even directed the Lyceum season in London.

In 1871 the premiere of Verdi’s opera Aida took place in Cairo, having been postponed a year due to the Franco-Prussian war. When Verdi’s favourite conductor (Mariani) was too ill to conduct, the important task fell on the worthy shoulders of Bottesini. The performances took place as part of the opening ceremonies for the Suez Canal and Bottesini was able to fit in a three day visit with Verdi at Saint ‘Agata in order to study the score. Much correspondence took place between Verdi and Bottesini. The first performance took place on December 24 to a crowd made up of the highest ranking dignitaries from most of the countries of the world, critics of all nationalities, as well as an enormous cosmopolitan crowd of spectators, all of whom greeted the work with enormous enthusiasm.

Verdi, who fully relied on Bottesini’s talent and ability, gave him in person, and in writing, the most detailed instruction. Although these performances of Aida made Bottesini—the conductor—a world wide figure, his main satisfaction on the personal level, was to see his reputation among the eminent artists and composers of his time increase tenfold and Verdi’s friendship and high regard for him grow and solidify in the most flattering manner.

Verdi wrote from Genoa in December 1871:

“Dear Bottesini,

“I cannot tell you how much I appreciated your kind thought in sending me a telegram after the first performance. This in one more instance in which you have obliged me, not to mention all the loving care you have invested in that poor Aida. Not only have you shown much eagerness but you have also displayed your extraordinary abilities in rehearsing and conducting, abilities which, of course, I have never doubted.

“Thank you, therefore, my dear Bottesini, for all you have done for me on this occasion; kindly also convey my sincerest thanks to all those who have taken part in the performance of this opera.”

The director of the Teatro Reggio in Tonno, where Bottesini often conducted, wrote:

“After the success of Aida, Bottesini received innumerable offers of Musical Directorships and conducting engagements but from that time on, although for financial reasons he could neglect neither the double bass or the baton, he chose to devote himself primarily to composition.

“Bottesini is not only a phenomenal virtuoso, but a consummate musician, a skillfull and fascinating conductor, and a composer with a naturally rich vein of Italian Melody, wedded to a profound musical sense, and an exacting knowledge of the orchestra.

“During rehearsals, he was never demonstrative and he never lapsed into sentimentality or affectedness when addressing the orchestra, nor did he show exaggerated impatience or haughty disdain. At most, there would be a short outburst, almost immediately repressed. When that happened, he would toss his hat up in the air or fling it onto the stage floor and that sufficed to calm him down.

“While conducting concerts and operas he always presented a dignified, composed, and gentleman like attitude following the traditions of the Italian school as imparted to us by Mariani and Pedrotti. His art in conducting relied mainly on the readiness, seriousness, and assurance of his beat and the careful choice of tempi, contrary to those conductors who, in order to appear inspired by the divine genius of art (even though they might be conducting a tiny orchestra) make themselves busy, standing up, bouncing, endlessly moving their bodies about like owls on a perch.”

A Barcelona critic remarked:

“Bottesini does not need to cause trouble and intreague [sic] among people to reign among Directors. He tries to win the affection of his subordinates by being an example for them in the arts and a father and a brother too without letting us forget that he honours the position he occupies (Music Director). Artistically speaking, it will be very difficult to fill that position again the day he leaves because we know of no one in Europe with all of his characteristics excepting Mr. Costa [later Sir Michael], Music Director of the great Covent Garden in London.”Bottesini continued to appear as a conductor for the rest of his life and was conducting at the Teatro Reggio in Parma in his last year. However, he did not, after his contract in Cairo expired, accept any further Music Directorships. One notable exception was a long season of opera in 1879 (including a performance of Ero e Leandro) in Buenos Aires followed by visits to Montevideo and Rio de Janeiro.

For conducting and service to music, Bottesini was given a number of honorary batons in silver, ivory, etc. as tributes of the esteem of musicians he conducted, as well as high honours from various countries and courts including: Chevalier of the Italian Orders of the “corona d’Italia, and the Santa Maurizio e Lazzano, Chevalier of the Portuguese Order of Christ and Saint Jago, the Imperial Turkish Order of the Medjidieh and Commander of the Spanish Order of Carlos III. The King of Spain also made him Commander of the Order of Isabel de Catolico.

Part 3 - Page 12

Bottesini’s musicality was well summed up by a Milan critic who was listening to a London performance and making a comparison of Sivori (the great violinist) and Bottesini.

“If one tried to describe the special prerogatives of their individual talents and their various effects of the souls and minds of those who listen to them, one could perhaps say that Bottesini’s understanding of art is more consistent and that with the simplicity, the purity and the intimacy of his interpretations, he produces sounds that are a joy to the ears and aching hearts of his listeners.”

The London Times published the following story:

“Being, besides a great artist, also a man of the world, and, moreover, kind-hearted and fond of humour, he had an inexhaustible store of anecdotes, the reminiscences of his travels, his triumphs, and his meetings with royal and other personages with whom, in the course of his artistic peregrinations, he had come in contact.

“On one occasion, after a concert he had given at the ‘Kursaal’ of Wiesbaden, an English lady, plainly dressed, approached him and said ‘Oh Signor Bottesini, I am charmed with your playing, and should be so glad if you would come some day soon and play at my house! Bottesini, thinking that the lady before him was one of the innumerable “Anglaises” to whose eccentric and extravagant displays of hero-worship he was so accustomed, simply bowed in silence. ‘Besides’ continued the lady, ‘I have heard you play before in London’. The artist smiled and bowed again. ‘Yes’ persisted the lady. ‘I heard you play at my mother’s.’ ‘And who’ Bottesini now rejoined ‘is your mother, madam, if I may ask?’ ‘The Queen of England’ was the quiet and placid reply: Whereupon it at last dawned on Bottesini that the lady before him was none other than the Crown Princess of Germany, then staying at Wiesbaden.”

In the course of his career as a performer, he earned astronomical amounts of money and yet, if not altogether poor, he certainly did not die rich, lie did not really comprehend the value of money. He endured deprivation with philosophical resignation while squandering his earnings with the most careless enthusiasm when times were better. Gold slipped through his fingers without him even noticing it. The money sometimes went on millionaire’s whims (while in Cairo at one time, he set up a complete menagerie of wild beasts!), or often to help friends in difficulty. He contracted debts more than once to oblige someone or satiate the greed of some adventurer. Bottesini was endowed with a generous heart but at the same time he was absolutely incapable of adapting himself to the circumstances of life. Disillusion must have made him bitter but not ill-natured, and he certainly did not learn from experience. He would withdraw in an ill-tempered self restraint, grumbling and cursing; but he emerged from these extremes even more confident and good natured.

Bottesini’s good nature can be seen in the following remarks: